|

Brassens

au Pays de Galles

in

Les Amis de Georges n°70, novembre-décembre 2002

Début

septembre 1970, tout seul à Paris, je préparais la soutenance d'une

grosse thèse. Je recevais de Cardiff, presque chaque

jour,

des feuilles tapées que je corrigeais, renvoyais... Puis,

grève

des postes - plus de feuilles, thèse en suspens. C'est à

ce

moment-là, par peur du vide,

que

j'ai songé à un projet que je

mijotais

depuis quelques années et

que la thèse avait écarté - un

livre

sur la chanson française que j'avais déjà enseignée à l'Uni-

versité

de Cardiff. Par où commencer, ou plutôt, comme tou-

jours,

comment me motiver ?

Choisissons, me suis-je dit, le plus grand et commençons par un

contact.

Avec la désinvolture et la confiance de mes trente ans, je fais

mes

recherches, trouve le numéro de Pierre Onténiente, lui explique

mon

projet au téléphone alors qu'il rentrait

justement de vacances.

Il

va en parler, dit-il, à Georges et me rappellera. Dès le lendemain,

Pierre m'annonce que Georges veut bien rencontrer le jeune professeur

anglais ; on pourra aller rue Santos-Dumont un

après-midi ; Pierre m'y conduira en voiture. La petite "Mini"

de

Georges embarque à son bord : moi, Christine - une amie qui sera

l'ingénieur

du son -, mon magnétophone, une longue liste de questions

soigneusement

préparées, et un grand chien affectueux qui a nom

Kafka.

Georges

vient à la porte nous saluer.L'effet du réel sur l'image médiatisée

peut être extraordinaire : on connaît cette voix, cette tête, et

pourtant l'homme à qui l'on serre la main n'est plus la vedette ; il

existe maintenant dans une autre dimension, comme nous existons pour lui

dans une autre dimension. On n'est plus un de ceux qui applaudissaient

et qu'il ne voyait pas parce qu'il avait

arrangé

les projecteurs justement pour éviter cela. Vous êtes deux

hommes

; il y a un abîme entre vous et il s'agit de construire un pont.

Pourquoi Georges a-t-il accepté ? Pierre m'a dit par la suite qu'il

recevait des centaines de requêtes identiques, de personnes bien plus méritantes

- me semblait-il - que moi. Je crois qu'il faut voir là la curiosité

humaine de Georges - observer un Anglais de près l'intéressait,

l'amusait, l'intriguait (c'est ce qu'il a dit plus ou moins à Louis

Nucera, voir Jacques Vassal Brassens ou la chanson d'abord,

p.303)(1). Et puis, comme toujours, le hasard : il rentrait de vacances,

il était disponible. Jamais un coup de téléphone n'abolira le hasard

; mais il peut parfois collaborer avec lui. Entre nous, ça a bien marché.

J'ai commencé

par quelques questions laborieuses mais les réponses sérieuses

et réfléchies de Georges m'intéressaient et peu à

peu

je laissai tomber mes notes et réagissai, essayant d'approfondir,

d'explorer.

Il a abordé des sujets qu'il n'avait pas, semble-t-il, évoqués

auparavant, notamment en ce qui concernait son désespoir à la Libération,

et la perte de sa foi en l'Homme.

Trois

heures plus tard nous nous séparâmes. On avait construit un

pont

ensemble avec des mots, des voix et. c'était tout de suite l'aventure !

Il fut convenu qu'il viendrait me rendre visite au Pays de Galles, avec

Pùppchen. "Pùppchen aimera ça, n'est-ce pas ?", a-t-il dit

à Pierre, surpris. Je ne me rendis pas compte à quel point il était

inouï que Georges, ce grand casanier, se lance ainsi dans

un inconnu gallois.

Un mois plus tard je les retrouvai à

l'aéroport de

Cardiff. Sur la route reliant

l'aéroport à mon domicile, il remarque

les maisons : "Bow-windows" fait-il, se souvenant soudain de

ses cours d'anglais à Sète! On joua les touristes : du magnifique château

fort normand de Caerphilly où

Georges fut surtout frappé par de petits

canards sur l'eau, aux rues de Cardiff

où Georges se promenait sans

que personne ne le remarquât - ce

qu'il n'avait pu faire depuis des années

! Il

fit connaissance avec ma femme, mon

fils, mes amis dont un grand violoniste

classique, Freddy Wang. On a

mangé, je crois, du gigot gallois et

de la cuisine chinoise.

Puis ils sont repartis. Il a écrit deux lettres

de remerciements, l'une à ma

femme,

l'autre à moi. La lettre adressée à ma femme avait la couverture

de

son premier disque d'adolescente : à seize ans, chez sa correspon-

dante

française, à Vichy elle avait découvert

Le Gorille et Hécatombe.

De

retour à son lycée gallois, son nouveau

vocabulaire avait un peu

choqué

l'admirable femme qui était son

professeur de français. Quant à

ma

lettre, elle contenait une page manuscrite,

tirée d'un cahier - un

poème

avec le refrain Mon pote le poète.

Après

ce premier séjour, Georges me

téléphonait assez

souvent et on discutait comme discutent des copains.

Il

nous envoyait des livres, sur Paris ou sur la langue.

Deux

ans plus tard, l'Université de Cardiff avait construit un nouveau

théâtre

et j'eus l'extravagante idée de demander à Georges de venir

chanter

pour l'inaugurer. Il accepta !

Cette

fois nous nous retrouvâmes à Heathrow. J'étais accompagné par

Jake

Thackray auteur-compositeur-interprète assurant la première par-

tie.

Jake est l'auteur de mer veilleuses traductions de Georges en

anglais

(notamment Brotber Gorilla). Comme il l'a dit plusieurs

fois

en public depuis, pour lui, qui adorait

Georges, cette expérience

relevait

au pinacle ! Apprenant, à sa grande surprise, que Georges Bras-

sens

venait en Angleterre, l'imprésario de Jake lui prête sa Rolls Royce

avec

chauffeur, et c'est ainsi que Georges et Pùppchen découvrirent

Londres

en Rolls, de nuit, émerveillés par tout, heureux comme des

enfants.

Nous descendons dans un vieil hôtel traditionnel de Mayfair,

Brown's,

et le soir, invités par Jake au célèbre club de Jazz Ronnie Scott's,

nous

allons applaudir la vedette de la soirée : Stéphane Grappelli. Grap-

pelli,

apprenant à l'entr'acte la présence de Georges dans la salle, croit

à

une blague, vient voir quand même, puis tombe dans les bras de

Georges,

les larmes aux yeux.

Jake

nous conduit le lendemain à Cardiff. Georges et Pùppchen dorment chez

moi. Pierre Nicolas nous rejoindra un peu plus tard. Nous préparons le

concert, choisissant un florilège de chansons (mon désir d'entendre Le

grand Pan ne fut hélas pas exaucé !). Karl Francis, cinéaste gallois

travaillant pour BBC2, me demande l'autorisation de filmer.Après une

courte hésitation, j'accepte, à condition toutefois que les caméras

restent invisibles. Le film fut

admirable.Ray

Brown, créant l'année dernière une émission de radio pour la BBC sur

la visite de Georges à Cardiff, a retrouvé ce film dans les archives.

M'interviewant

pour son émission, Ray me demande de lui dire ce que

je

ressentais au Sherman ce soir-là. Lui décrivant mon état de "

stupé-

faction,

de délire triomphal ", j'ajoutai : " J'étais ravi par tout

ce qui se

passait;

nous étions heureux ".

Il restait

une dernière entorse aux habitudes de Georges. Brassens exerça une

pression sur Philips pour que sorte le disque de l'enregistrement fait

ce soir-là. C'est grâce à cela que nous avons le seul disque live de

Brassens, qui est aussi une sorte de "Best of" :

"Brassens in Great Britain" (l'enregistrement de la première

partie - Jake Thackray - du concert n'a jamais été publié).

(1) La modestie de Colin Evans lui fait omettre de rapporter que

Brassens, d'après Vassal, aurait dit "...comme il est charmant,

comme il est gentil, j'ai marché".

|

Brassens

in Wales

Early September 1970: I was alone in Paris finishing off a thesis.

Almost every day I would get from Cardiff a parcel of typescript which I

would correct and send back to the typist. Then there was a postal

strike– no more pages, thesis in the air. That was when, from fear of

having nothing to do, I thought about a project which I had been mulling

over for years and which the thesis had put on the back burner. The idea

was a book on the French chanson which

I had already been teaching at Cardiff University.

But where to start and, as always, how to get the motivation?

Let’s start, I told myself, at the top and by a personal contact. With

the carefree confidence of the 30 year-old I looked things up, found the

phone number of Pierre Onteniente, spoke to him on the phone –the day

after he got back from holiday – and explained my project. He said he

would speak to Georges and call me back. The next day he called and said

yes, Georges would like to speak to the young English teacher; we could

go rue Santos-Dumont in the afternoon; Pierre would drive me there.

Which he did – into Georges’s Austin Mini he squeezed me, my

taperecorder, a friend Christine who would do the recording, a long list

of questions I’d prepered and a big affectionate dog called Kafka.

Georges came to the door to greet us. The effect which reality has on

the media image is astonishing: you know the voice, the face - and yet

the man whose hand you shake is no longer the star; he exists in another

dimensiuon – as we exist in another dimension for him. We are no

longer one of those who clap and cheer and whom he never sees because he

arranges the lights deliberately at eye-level to prevent him seeing.

There are two of you; there’s a gulf between you and you need to build

a bridge.

Why did Georges agree? Pierre

told me later that he got hundreds of similar requests – from people

much more deserving (it seems to me) than I was. I think it was

Georges’s human curiosity – to see an Englishman close-up interested

him, amused him (This is more or less what he told Louis Nucera, see

Jacques

Vassal Brassens ou la chanson d'abord, p.303 ). And

then – as ever – sheer luck: he had just got back from a holiday, he

was available: chance and my phone call worked together. And we hit

it off. I began by asking

my rather heavy-handed questions but Georges’s serious and throughful

answers interrested me and I began to abandon my notes and to react, to

take him further, to explore with him. He told me things which he had

not said, it seems, previously – particularly his despair at the time

of the Liberation of Paris and the loss of his faith in mankind.

Three hours later we separated. We

had built a bridge with words and voices and over it we proceeded to

skip. We agreed he and Pupchen would come to Wales to visit me.

‘Pupchen would like that wouldn’t she?’ he said to a surprised

Pierre. I didn’t realise how amazing it was that Gerges, the great

stay-at-home, should leap like this into a Welsh unknown.

A month later I met them at the airport in Cardiff.

On the way to my house he noticed the houses: ‘Bow

windows’ he murmured,

remembering suddenly his English lessons at Sète. We did tourist things

– the great Norman castle at Caerphilly where Georges was struck

mainly by a flotilla of ducks on the moat, the shopping streets of

Cardiff where Georges walked without anyone recognizing him –

something he had not done for years. He met my wife Carol and my son

Nick, my friends, including a great classical violinist, Freddy Wang. We

ate Welsh lamb I think and Chinese.

Then they left.He wrote two separate letters of thanks, one to Carol and

one to me. Hers had the cover of the first record of his she had owned;

at 16 staying in Vichy with her pen-friend she had discovered Le Gorille

and Hecatombe. Back in her Welsh Grammar School her new vocabulary had

shocked the admirable lady, Miss Rees, who taught her French.

Mine contained a manuscript page, torn from a notebook – a poem

with the refrain ‘Mon pote le poète’.

After this stay he phoned me often and we would chat. He sent us books,

about Paris or about language.

And then, two years later the University of Cardiff built a new theatre

and I had the wild idea of asking Georges Brassens to come and do a

concert to inaugurate it. He agreed.

This time we met at Heathrow. I was accompanied by Jake Thackray who was

going to sing the first half. Jake

is the author of marvellous translations of Brassens. As he said many times in public, for him it was the summit of

his career. Learning to his

great surprise that Brassens who never left France was coming to Britain,

Jake’s agent loaned him his Rolls and chauffeur, and it was in a Rolls,

at night, that Georges and Pupchen discovered London for the first time

in their lives, amazed at everything, happy as children We stayed in an

old traditional hotel in Mayfair, Browns, and in the evening, Jake

invited us to Ronnie Scott’s. The star that evening was Stéphane

Grappelli. Grappelli learned in the interval that Georges was in the

audience, and, thinking someone was pulling his leg, came out to see. He

fell into Georges’s arms, tears in his eyes. They had known hard times

together.

Jake drove us to Cardiff the next day.

Georges and Pupchen stayed with me. Pierre Nicolas, the

bass-player came later. We

prepared the concert, choosing songs which are a sort of ‘Best of

Brassens’ (something Georges never did). We had to choose the ones he

still knew by heart. The BBC learned what was happening and Karl

Francis, a Welsh film-maker working for BBC2, asked if he could film the

concert. I said no at first, then Georges said why not and I said yes

provided the cameras were discreet. Which they were and the film was

excellent. Ray Brown who

made a radio programme last year on Georges’s visit was able to find

it in the BBC archives. Interviewing

me for this programme Ray asked me what I felt at the Sherman that night

and I replied that I was ‘in a state of amazement, of triumphant

delight – delighted at everything that had happened; we were happy.’

Georges made one more exception to his rules. He convinced Philips to

issue a record of his part of the concert. That is why we we have the

only live recording of Brassens - Brassens in Great Britain 832.268

Now in a CD box set - 11, 836-2992 with a few extra songs.

Jake’s part of the concert has not been published.

(1) Being modest, Colin Evans skips Brassens' sentence, as noted by

Vassal : "...as he's a charming person, as he's nice kind, I went

for it" |

Jake

Thackray

in Les Amis de Georges

n°73, mai-juin 2003

Jake

Thackray est mort le 24 décembre 2002, à l'âge de 64 ans. J'ai

raconté

dans le numéro 70 des Amis de Georges comment en 1973 Jake a

organisé

avec moi le voyage de Georges et de Pùppchen à Londres et

à

Cardiff. Jake a chanté la première

partie du

concert de Cardiff - ses

propres

chansons et une de ses traductions de Georges - Brother Gorilla.

Il

a souvent répété par la suite, notamment au cours d'une interview

don-

née

à la BBC en 2002, que ce fut l'apogée de sa carrière.

Ses

traductions sont de loin les meilleures en langue anglaise, parce que

lui-même était un auteur-compositeur de génie. Ses chansons,

comme

celles de Georges, sont ancrées

dans un terroir à la fois réel

(le

Yorkshire) et imaginaire (folklore et

littérature). Les journaux ont parlé

de

Noël Coward; mais il fallait plutôt dire

que Jake fut le Brassens anglais -

même

humanité, même humour, même

manière de raconter, même

maîtrise

de la langue et mêmes liber tés

prises avec elle. Mais là où le

génie

de Georges œuvrait dans une longue

tradition ininterrompue, en

Angleterre

Jake travaillait toujours à contre-courant.

Sa relation

à Georges est curieuse et touchante.

Georges lui a rendu visite,

à

Monmouth, en 1973 après le concert

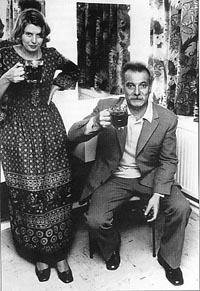

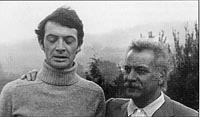

(le numéro 70 montrait une

photo,

prise ce jour-là, où Jake a les yeux

fermés comme s'il croyait

rêver).

Il a par la suite été plusieurs fois

rue Santos-Dumont ; Georges a

écouté

ses chansons, appréciant la

musique, ne

comprenant guère les

paroles.

Lors d'une interview en 1971 Jake

m'a dit, parlant de ses séjours

comme

professeur d'anglais, en Algérie

et plus tard à Lille, «J'étais ivre de

la

langue française et puis je suis tombé amoureux de Georges Brassens

que j'ai entendu, comme ça, à la radio». C'est là l'expérience de

beaucoup d'étrangers francophiles. Mais Jake avait sa propre ambition,

sa

propre

langue, ses propres histoires, et il ajouta : «Ça m'a rendu fou. Je

l'ai

tant

écouté. Maintenant je devrais commencer à m'écouter moi-même

davantage».

Cela explique peut-être son ambivalance à l'égard de la traduction :

je

n'en

connais que trois qu'il a enregistrées, Le Gorille, Marinette, Je

rejoin-

drai

ma belle - devenues de merveilleuses chansons... anglaises. Mais

je

suis sûr qu'il en a fait d'autres qu'il ne

chantait pas de peur de ne plus

entendre

sa propre voix, un peu comme

Virginia Woolf quand un jour

elle

lut Proust et faillit désespérer. Lui qui

traduisait si bien Georges me

déclara:

«On ne peut pas l'exporter. Je crois

qu'il est simplement là. Tout ce

qu'on

peut faire c'est de se mettre sous

le grand chêne et regarder tom-

ber

les glands. Instinctivement, quand

on aime quelqu'un on dit Je

vais

te présenter aux gens de chez

moi, je vais te

faire passer. Je pense

que

c'est une erreur. On ne peut jamais

le faire connaître comme ça».

Heureusement

Jake n'a pas été conséquent

et il ajouta : «Mais je n'ai

pas

pu m'empêcher». D'où le concert de

Cardiff et ses traductions. Mais il y

aurait

davantage à dire sur l'influence de

Georges sur les autres composi-

teurs.

La

cérémonie d'adieu eu lieu au Pays

de Galles, dans la petite église

catholique

de Monmouth à laquelle Jake était fidèle. Des amis étaient

venus

de loin (dans le temps et dans l'espace) ; certains montèrent en

chaire,

parlèrent de lui, émus, racontèrent des histoires (le prêtre en

avait

une

qui était spécialement drôle). A la fin on entendit la voix enregistrée

de

Jake qui chantait The Last Will and Testament of Jake Thackray -

pas une traduction mais certainement un hommage au Testament de Georges.

Il

demande aux copains d'appeler d'abord le prêtre et puis d'aller cher-

cher

à boire : «Dites une prière ou deux pour mon âme mais vite les gars,

vite

: que la fête commence». Chanson qui, comme celle de Georges,

paraissait

ironique, drôle, généreuse quand

l'auteur, bien vivant, la chan-

tait

en souriant sur la scène du Sherman. Elle l'était toujours d'ailleurs,

dans

cette église que son cercueil venait

de quitter (Viens pépère...'). En

l'écrivant

il y a trente ans, quand le chêne

était encore debout, Jake a

certainement

dû penser que, l'heure venue,

l'on ne manquerait certaine-

ment

pas le coup de l'enregistrement.

Mais quelle émotion aujourd'hui à entendre

cette voix, si guillerette, nous inviter à

festoyer sans lui. Dieu, que

le son du magnétophone est triste...

Et

pourtant, invités non seulement par lui

mais aussi par sa veuve Sheila

et

ses trois fils, Tom, Bill, Sam, nous nous

dirigeâmes à pied vers le pub

auquel

Jake était également fidèle.

Cheers,

Jake, adieu et merci.

|

Jake Thackray

Jake Thackray died on Christmas Eve 2002, aged 64. I described in Number

70 how, in 1973, Jake organised with me the trip which Georges Brassens

and Puppchen made to London and Cardiff. Jake sang the first half of the

Cardiff concert – his own songs and one of his translations of

Brassens Brother Gorilla. He

often said (for example in an interview given to the BBC in 2002) that

it was the high spot of his career.

His translations are easily the best in English because he

himself was a songwriter of genius. His songs, like those of Georges,

are rooted in a place which is both real (Yorkshire) and imaginary

(folklore and literature). The press invoked Noel Coward but they should

have said Jake was the English Brassens – the same humanity, the same

humour, the same way of telling a story, the same mastery of language

and the same liberties taken with words.

But while Georges’s genius operated within a long,

uninterrupted tradition, Jake, in England, worked against the grain.

His relationship to Georges is

strange and touching. Georges visited him, in Monmouth, in 1973 after

the concert (Number 70 had a photo, I took that day in which Jake has

his eyes closed as if he thought he was dreaming). Jake visited Georges

at his home in the rue Santos-Dumont in Paris, on several occasions;

Georges listened to Jake’s songs, enjoyed the music but did not

understand much of the words. In a conversation with me in 1971 Jake

described how, when he was an English teacher in Algeria and then in

Lille, he was ‘drunk on the French language’ and how he ‘fell in

love with Brassens’ when he happened to hear him on the radio.

Many francophiles will recognise this experience. But Jake had

his own ambition, his own language, his own stories and he added: ‘It

drove me crazy. I listened to him so much. Now I should start to listen

to myself more’.

That explains perhaps, his ambivalence about translating Brassens. I

only know three songs recorded by him: Le

Gorille, Marinette, Je rejoindrai ma belle – all three are

marvellous English songs. But

I’m sure that he made other translations which he did not sing from

fear of not hearing his own voice, rather like Virginia Woolfe when one

day she discovered Proust and almost despaired. Jake who translated

Brassens so well declared: ‘You

can’t export him. I think he’s just there. All you can do is stand

under the great oak tree and watch the acorns fall. Instinctively when

you love someone you say I’m going to take you home and show you to the folks; I’m going to

take you there. I think

that’s a mistake. You can’t know him like that’.

Fortunately he wasn’t consistent and he added But I couldn’t stop myself. Hence the concert at Cardiff and the

translations. But one could say a lot more about Georges’s influence

on other songwriters.

The farewell ceremony took place in Wales, in the little Catholic Church

of Monmouth to which Jake was faithful.

Friends had come from a long way off (in time and place) some of

them stood up, spoke of him movingly, told stories (the priest had a

particularly funny one). At the end we heard Jake’s recorded voice

singing Last Will and Testament

– not a translation but certainly homage to Georges’s Testament. ‘Say a prayer or two for my soul then get the booze

boys’. It’s a song, like Georges’s, which sounded ironical, funny,

generous when he sang it on the stage of the Sherman in Cardiff.

It still was in this church from which his coffin had just

departed. Writing it thirty years ago Jake must have thought that

someone would have the idea of the recording.

But it was almost unbearable to hear that cheerful, lugubrious voice

inviting us to drink without him.

And yet, invited by him but also by his widow Sheila and his three sons,

Tom, Bill, Sam, we made our way up the road to the pub to which Jake was

also faithful.

Cheers Jake. Goodbye and thank you.

|